Thinking of mid-century British designers, names that come to the mind might include Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden. Less so Barnett Freedman who, despite a proliferation of design work that spanned Transport for London posters, book jackets and royal commissions, has gone relatively under looked.

That might change with a new exhibition, Barnett Freeman: Designs for Modern Britain, held at Pallant House Gallery this March. The exhibition’s curator, Emma Mason, tells Design Week that the time had come for Freedman’s work to be given its due. She attributes it to a growing exploration into the period’s work, as well as renewed interest in the techniques Barnett used such as lithography and print-making. (There’s also a personal touch: Freedman’s son, Vince, is in his 80s now, and a lot of his recollection of his parents proved invaluable in building a picture of his father.)

Freedman was born in 1901 in East London to Jewish immigrants from Russia, and although he was “comfortable” with his Jewish heritage, Mason says that it didn’t play an enormous role in his work. Despite living through World War II, his “optimism” drove his outlook: “He always believed people were good.”

That comes through in his work, particularly with book jacket design. His first major commission in 1931, for publishers Faber & Faber was to design and illustrate Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer. This sparked a trend; he went onto design jackets for Oliver Twist, Wuthering Heights, War and Peace and Anna Karenina. Those final two are recognised as some of the finest examples of 20th century book design. What made him stand out, Mason says, is that he was a “supreme master of lithography”.

It meant he could “cross boundaries between art and design”, she adds. Mason says: “He could draw or paint a beautiful image, but then he had all the technical ability to transpose it to stone for it to be made into a lithograph and reproduced in its hundreds or thousands.”

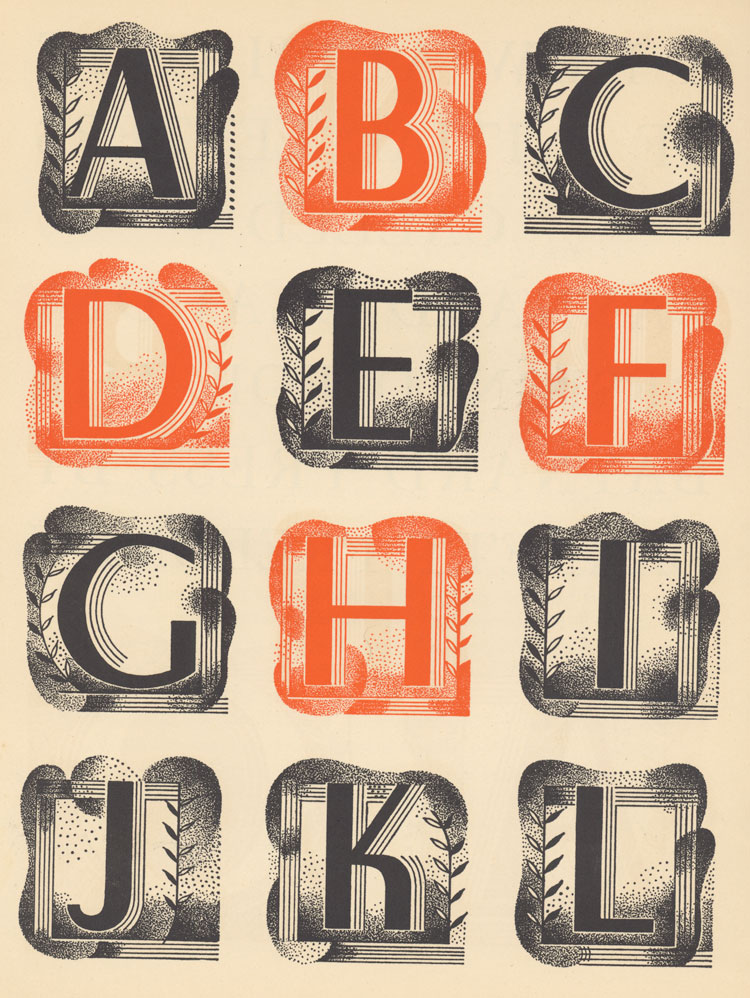

He picked up that skill from his varied educational background; he trained as an apprentice at a printmakers and also at an architectural practice, which is where he developed his skill at lettering. But he also studied portraiture and painting at the Royal College of Arts, lending his design work a fine art quality. Accompanied with those skills was a sense of “humanity”, Mason adds. The book jackets, as well as inventive use of type, feature prominently the iconic characters’ faces. Being able to transfer his art to lithography (a method of reproducing prints by using stone) meant he was able to retain all those details. Freedman also cared how the books were designed on the inside, too. His work on illustrations, as a vital accompaniment to text, was influential for book designers after him, according to Mason.

Freedman’s son Vince recalls his love of people, and their stories and capturing a sense of their personality. It’s what served him well as an Official War Artist during World War II – which includes first-hand illustrations of the aftermath of the D-Day landings – where Mason says he was more interested in “people’s faces than their rank”. Despite his Jewish heritage, the time spent aboard submarines and among soldiers, was happy for him, she adds.

The exhibition brings together a lot of Freedman’s work for the first time, placing his lesser-seen oil paintings next to his commercial work. Some of that latter body of work is very recognisable: his posters for the London Underground, for example, have been widely reproduced. It is a fitting way to appreciate Freedman’s work, according to Mason. “He gave the same amount of attention to designing letterheads for a biscuit manufacturer as he did a large Transport for London poster,” she says. By embracing commercial work, Freedman was also able to focus on passion projects as the financial freedom enabled him to do smaller, less well-paid projects like illustration.

As Mason says, “he saw no difference between commercial work and fine art”. And Freedman made his views on commercial work public, by writing about it for publications like The Penrose Annual and Signature. His nickname at the RCA was also Soc, short for Socrates, because he was always debating with people. About his lithographic work, Freedman himself said: “The direct outcome of the work of original artists on lithographic stones are works of art in their own right.”

However a lot of the commercial work, despite its distinct styling, is relatively anonymous. People might recognise the designs, but they won’t necessarily associate it with Freedman’s name. That might explain why he has gone relatively underlooked compared to his contemporaries, Mason says. Neither does it help that he died young. Plagued by respiratory problems, Freedman spent a lot of time in hospitals as a child, where he learned to read, write and play music with the help of doctors and nurses. The asthma-related illness never went away, though: He continued to spend time in hospitals throughout his life and eventually died of a heart attack in 1958. Mason says that if he hadn’t have died so young, the work he would have gone onto do would have cemented his status as one of Britain’s most influential designers.

A clue as to what that potential work – and its widespread appeal – might have looked like can be seen in his final projects. In 1953, he was chosen to design The King’s Stamp, a commemoration stamp for King George V on his silver jubilee. He would also go onto design a stamp for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Like a lot of his work, The King’s Stamp started as a lithograph before it was mass-produced which mean that there was an “awful lot of detail” in it, Mason says. “The edges are full of little details, which is a very Barnett Freeman design, and they were quite different to stamps that had gone before,” she adds. It sold in its millions, and a newspaper of the day commented that Freeman was the world’s biggest-selling artist because of it. The Post Office also believed it be an important design – they filmed the process of him making it.

It is perhaps his final project, poster work for Guinness, that sums up Freedman best. He was brought in every month to advice the company’s executive on arts and letters, and provide wider context about why it was so important that businesses and the government support the arts. His poster designs for the alcohol company – once again, based on lithography and featuring everyday scenes of darts and football – were displayed in pubs to celebrate the launch of the Guinness Book of World Records. “Working with executives at Guinness, and in the studio with art technicians and lithographers, as well as designing for audiences at the pub,” was a happy combination for Freeman, Mason says. And though his life was cut short, that final project “fit him perfectly”.

Barnett Freedman: Designs for Modern Britain runs from 14 March – 14 June 2020 at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, PO19 1TJ.

The post Barnett Freedman “saw no difference between commercial work and fine art” appeared first on Design Week.

from Design Week https://ift.tt/2v4gXT2

No comments:

Post a Comment